Music: Traditional Forms

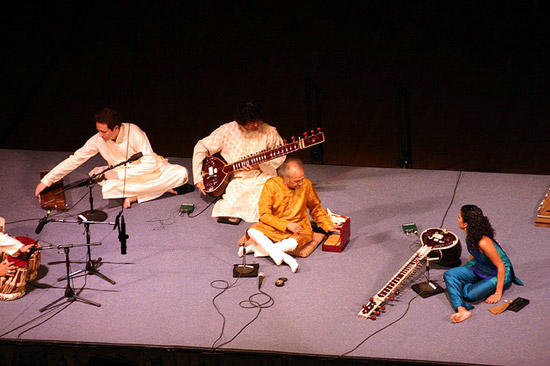

Classical

Indian classical music is divided by region into Hindustani (North Indian) and Carnatic (South Indian) styles. In both cases, though instrumental performance is both an ancient and a significant component of shastriya, vocal performance is considered primary. Therefore the concepts are described in terms of the voice, and instruments are revered according to their capacity to emulate vocal qualities (such as meend, or slides).

Notes and Scales

Dhwani is any sound, and nada is a pleasing sound. A nada of a specific, melodious character is a swar (note). The basic seven swars (sargam, collectively) and their short forms are: Shadja (Sa), Rishabh (Re; Ri in Carnatic), Gandhar (Ga), Madhyam (Ma), Pancham (Pa), Dhaivat (Dha), and Nishad (Ni). These swars are, in their pure forms, called shuddh swars. Sa and Pa are achala (fixed) swars, never deviating, while the rest are chala (movable) swars; Re, Ga, Dha, and Ni have komal (soft/flat) forms, while Ma becomes tivra (sharp). So there are 12 swars—seven shuddh, four komal, and one tivra— and a group of any seven swars is a saptak. There are three saptaks (scales/octaves): mandra (low), madhya (middle), and tar (high).

Classes of Raga

Raga is a melodious arrangement of five or more swars that are rendered in an aaroha (ascending) and avaroha (descending) order. The number of swars in a raga determines the jati; an Audhav jati raga has five swars, a Shadhav jati raga has six swars, and a Sampoora (complete) jati raga has sevenswars. These basic jatis combine to form more complex jatis; for instance, a raga with five aaroha swars and seven avaroha swars is of the Audhav-Sampoorna jati.

Building the Raga

Each raga belongs to a parent scale called thaat (mela in Carnatic), and has a vadi (main) swar and a samavadi (supporting) swar; the remaining are called anuvadi swars. Certain swars, not occurring in the raga, but introduced for effect, are called vivadi swar. A raga must contain either the Ma or the Pa swars, and two forms of the same swar (shuddh and komal or shuddh and tivra) cannot follow each other—although there are exceptions like the shuddha Ma and tivra Ma in Raga Lalit. Pakad is the swar arrangement introducing a raga, and alankars are swar variations and ornamentations—like meend, which is sliding from one swar to the next, and sparsh, where a swar is lightly touched upon—used in rendering the raga. The perceptible space between two swars is called a shruti; traditionally there are 22 shrutis.

Performing the Raga

A raga performance begins with an improvised alap/vistar in vilambit laya (slow tempo), elaborating the swars in the raga, sometimes to the accompaniment of the tanpura drone or jivari (sustained resonant tone to guide the vocalist). The tabla comes on with the bandish/gat (fixed composition), which may be in madhya laya (medium tempo) or drut laya (fast tempo), and continues to keep time with the bol (beat—literally word or syllable) and the tan (phrase), both of which improvise on the bandish and are sung in aakar (without pronouncing words—by extending the vowel aa) in drut laya.

Rhythm of the Raga

Tala, the rhythmic pattern of the raga, is denoted by a cycle of beats called avartan. Each beat is called bol, theka, or akshara; a tala is distinguished by the number of thekas and the vibhaag (division) of these thekas; dhamar tala, for instance, has 14 thekas divided into four vibhaags, as 5-2-3-4. Sam is the first theka of any tala—denoted with a handclap or an emphasis on the tabla, mridang, or pakhwaj—and the first theka of the second or third vibhaag is usually the khali (empty), indicated without a percussion beat or by waving the hand to the side. The tala pattern remains the same even when the pace of the laya changes. The performance of a section or set of phrases is usually rounded up with a tihai—a triple repetition of a phrase in which the third repetition ends neatly on sam.

Raga Mood and Seasons

Each raga is associated with a specific rasa (mood/emotion): shanta (peace/calmness), karun (sad/compassion), shringar (romance/beauty/art), veer (pride/courage), rudra (anger/destruction), hasya (laughter/joy), adbhuta (wonder/mystery), bhayanaka (fear/worry), or vibhatsa (disgust/self-pity). In Hindustani classical music, each raga is assigned a specific samay (time), either of the day or a particular season. A raga performed in its particular time is considered more effective in evoking its specified rasa—Raga Malhar in the monsoon season, for instance. The midnight-to-noon portion of the day forms the Poorvanga (first), and the ragas sung in this period are called Poorva ragas; noon to midnight forms the Uttaranga (second), when Uttar ragas are sung. The 24 hours are also divided into 8 prahars (time units) of 3 hours each, starting from 4 am. This system became codified during the Mughul Period, when the courts of the North Indian rajas supported Hindustani master musicians; Carnatic music is not usually so time-bound.

Apart from purely classical performances, ragas are utilized in Natyasangeet (musical dramas), kajris (rainy season folk songs), thumris (romantic songs about Krishna), and other semiclassical genres.

Gharana System

Within the traditional guru-shishya system of musical training, the shishya (student) lived, studied, traveled, and performed with the guru for many years, imbibing his or her technique and ideology and subsequently carrying it on. It was the guru who determined the student’s readiness for public, and later solo, performance.

In the modern era the guru-shishya system is still upheld, more or less, though with some modifications: for example, it is less typical for students to live with their teachers (unless, as is not unusual, they are the actual children of their teachers rather than ceremonial “adoptees”), and demands for constant practicing—as much as 18 hours a day in previous generations—are more likely to be reduced to 6 or 8 hours per day.

Alongside the formalized guru-student relationship of intensive one-on-one devotion and training, it is today common, whether through group classes or private sessions, for teachers to train students more along the lines of other forms of study. This follows the tendency in modern India, as elsewhere, for outside activities (for example jobs or university study) to compete with the musical training, which was formerly regarded as the sole appropriate pursuit, once entered into. This development has the benefit of allowing a wider population to partake in serious musical study, even if their aim is not necessarily to perform professionally. And, though the masters of earlier generations are still legendary for their wizardry, it would be difficult to argue that the quality of playing among modern performers has dropped in any discernible way (except, perhaps, to the now-unattainable ears of those departed wizards).

Each gharana maintained its distinct musical style, and in earlier times there were few interactions between different gharanas; musicians were discouraged from playing or even listening to music from another gharana. With the advent of All India Radio in the 1930s (through which, from the early days, top musicians were contracted to perform for daily broadcasts), this began to change, and much more so when recordings and film music became widely available. By the 1960s, collaborations between musicians of different gharanas became less unusual. In recent decades, of course, Hindustani musicians of all gharanas have collaborated frequently with each other, as well as with Carnatic musicians, and with Western musicians and performers from other major world traditions (Persian, for example). Even so, the gharana tradition continues, with distinctions maintained and transmitted by their lineage holders.

An Exemplary Lineage

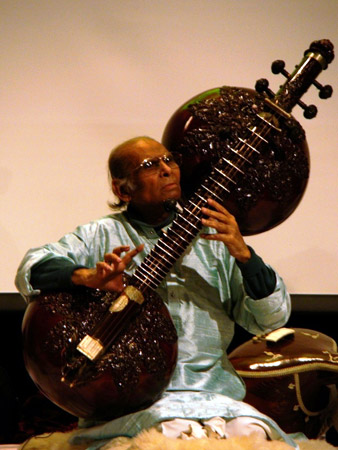

Ustad Allaudin Khan (a.k.a. Baba) of the Maihar Gharana studied under many gurus, notably Wazir Khan Baenkar, a descendant of Tansen and of his Senia Gharana. Baba annoyed the purists when he incorporated diverse musical elements in his style, and encouraged his students to listen to a wide range of music and to innovate. A tough taskmaster and a multi-instrumentalist, in the 1920s Baba formed the Maihar Band, which played his arrangements and compositions of Indian music using both Indian and Western instruments; in 1955 he established the Maihar College of Music.

In between, beginning in the 1930s, Baba trained students who went on to become some of the most prominent musicians of India. Among them were Nikhil Banerjee and Pandit Ravi Shankar (sitar); Pannalal Ghosh (flute); Baba's daughter Annapurna Devi (surbahar); Baba's nephew Ustad Bahadur Khan, and his son Ustad Ali Akbar Khan (sarod). The latter (known to his students as Khansahib) would in turn become the lineage holder of the gharana, eventually training literally thousands of musicians—many through the Ali Akbar College of Music, which he established first in Calcutta, and later in San Rafael, California—and achieving international renown for his compositions, recordings, and concerts. Since his passing in 2009, Khansahib’s youngest son, sarodist Alam Khan, has assumed the mantle of the Maihar lineage, while older son Ustad Aashish Khan (also an acclaimed sarodist) similarly continues performing and teaching within the traditions of the gharana.

Hindustani Forms

Dhrupad

The ancient dhrupad vocal form (Dhruv is the polestar, and pada means words) is associated with the veer rasa (courage/heroic) and is devotional in nature, glorifying Hindu deities. The vistar section in dhrupad begins with the syllables om, nom, thom rendered with slow elaboration, and the performance then accelerates to the jor (steady rhythmic section) and jhala/nomtom (fast rhythmic section). Commonly employed talas are shultal (10 beats), jhaptal (10 beats—composition called sadra), chautal (14 beats), dhamartal (14 beats—composition called dhamar), and other talas of the pakhwaj tradition. Instruments like pakhwaj, mridang, rudra veena, and tanpura accompany the singers. Dhrupad was very popular in the Moghul court, but the khayal overshadowed it in the 18th century. The Dagar Brothers of the Dagar Gharana revived public interest in the genre after a series of foreign concerts in the 1960s. The Gundecha Brothers and Ritwik Sanyal are also well known as dhrupad performers.

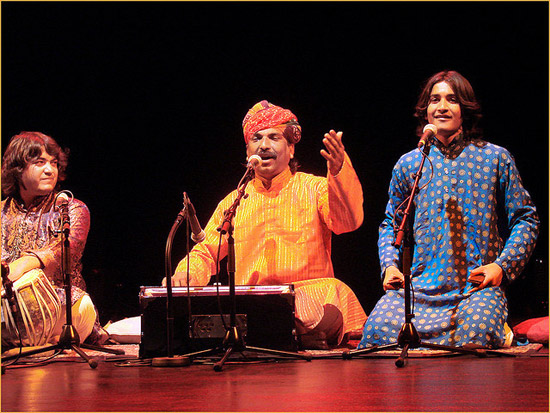

Ghazal

A ghazal consists of rhythmic couplets, with a refrain, utilizing the same meter for all the lines. The poetic form arose from the Persian qasida in the 6th century, and the Islamic incursions of the 12th century brought it to the Indian subcontinent, where, along with Persian and Urdu, compositions in regional languages became popular. The themes are often melancholic, written from the perspective of a lover yearning after an unattainable ideal—which can be interpreted as a longing for God. The sophistication of ghazals made them the preserve of the educated elites of the royal courts; the genre did not gain widespread popularity until the lyrics became more accessible in modern times. Famous ghazal composers include Rumi, Hafiz, Iqbal, Mirza Ghalib (by a tradition known as takhallus, the poet’s name is mentioned in the last verse)—and well-known performers include Pankaj Udhas, Jagjit Singh, Mohammad Rafi, and Hariharan.

Khayal

Khayal means imagination, and, while the text and raga of this vocal form remain the same as in other forms, the short bandishes (compositions) can be rendered in a free, flexible manner, with plenty of improvisation in the way the words, swars, syllables, and melodies are performed. A khayal performance usually begins with a short alap, followed by a bada khayal in vilambit laya (slow tempo) and then the chhota khayal in drut laya (fast tempo), with a thumri or a tarana at the end. The harmonium, tabla, or violin provides musical continuity each time the singer pauses. The themes include seasons, romance, spirituality, the antics of Krishna, and other aspects of life. Kishori Amonkar, Pandit Bhimsen Joshi, Pandit Omkarnath Thakur, Girija Devi, and Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan are renowned vocalists in the khayal style.

Bhajan

The devotional bhajans praise or describe deities like Ram and Krishna, extol lines from the scriptures, and impart the teachings and compositions of Mirabai, Tulsidas, Guru Nanak, Kabir, and Surdas. Regional bhajan styles and languages vary, but they all have a sthai (first section) and an antara (following sections), with the composer/poet’s name mentioned in the last antara. The songs are sung solo or in a group, with or without instrumental backing, and may be performed at any time, during leisure, social events, religious gatherings, or work. If instrumentation is used, the ektar, dotar, sitar, manjira, kartal, dholak, and tabla are traditionally popular, and, since its introduction in the mid-19th century, the harmonium has been used with great regularity. Some well-known bhajan singers are Anoop Jalota, Manna Dey, Lata Mageshkar, Bhimsen Joshi, and Parveen Sultana.

Tarana

In Persian, tarana (tillana in Carnatic) means "song." An invention of Amir Khusro, the tarana uses meaningless syllables and words known as nom tom in short bandishes that can be rendered in various styles and layas, and with flourishing tihais, to the accompaniment of the tabla, pakhwaj, and sitar. Ustad Amir Khan, Kumar Gandharva, Pandit Krishnarao, and Ustad Rashid Khan are some leading tarana singers.

Kirtan

The devotional kirtans are made up of mantras and hymns set to the rhythms of mridang, pakhwaj, kartala, harmonium, and tabla. Kirtankari is popular in Maharashtra, Punjab, and in many other parts of India.

Carnatic Music

In Carnatic music, the melakarta system classifies 72 janaka (parent) ragas—Todi, Kalyani, and Mayamalavagowla, for example—and various derivative janya (child) ragas—Bhairavi, Hindolam, Abhogi, and many others. Carnatic raga compositions are typically short and fixed, with faster tempos than in Hindustani music; though romance is among the lyrical subjects, themes are often elevated—invocation of deities, religious devotion, or descriptions of gods and temples, for example. The recital usually begins with varnam, a short, fast-paced, and vocally complicated piece that describes the raga.

The different varnam sections are pallavi(lyrical first section detailing main theme), anupallavi (second section detailing a related theme), mukthaayi swaram (syllables or swars), several charanams(lyrical end sections related to the pallavi or anupallavi themes), and chittai swarams(improvised swars). These are sung in order and usually set to aditala(8 beats) or atatala(14 beats). The varnam may be followed by an aalapanai(improvisation using swars from the raga), niraval (a song line or portion sung in different tunes within the given ragaand tala), or kalpanaaswaram(improvised swaras of the raga).

Kritis/keerthanams, devotional songs with fixed compositions, are sung next in different ragas and talams. Each kriti has pallavi, anupallavi, and charanam sections. Aswarajathimay also be sung; here, different swars are used in the charanam. Theragam thanam pallaviis usually present in most recitals, where the ragam elaborates on the raga, the thanam is the rhythmic rendition of the syllables tan, na, and nom, and the pallavi lyrics are tala-based and rendered according to the performer’s sense of rhythm.

The recital ends with slokas, bhajans, guru vandana (praise), and thillanas. The mridangam, pakhwaj, ghatam, morsing, kanjira, veena, tanbura, violin, and flute are the most usual instruments used (though others occur as well—for example, the renowned Kadri Gopalnath has successfully adapted the alto saxophone, and U. Srinivas the mandolin, to this extremely rigorous music). Tyaagaraaja, Muttuswami Diikshitar, and Shyaamaa Shastri were the foremost Carnatic composers, and renowned Carnatic musicians include M. S. Subbulakshmi (vocal), N. Ravikiran (gottuvadyam), L. Subramaniam (violin), G. Harishankar (kanjira), and E. Gayathri (veena).

Folk Forms

Lavani

The lavani style arose during the Peshwa rule in Maharashtra. A mix of song, dance, and theatrics on the themes of sex, politics, social customs, and religious beliefs, often presented in an arch or satirical manner, lavanis are traditionally performed by women in navwari (nine-yard) saris and gunghroos (anklet bells), with male singers providing a chorus, and to the instrumental accompaniment of tabla, harmonium, dhol, and daf. Honaji Bala and Ram Joshi well-known lavani composers, and performers include Yamunabai Waikar and Surekha Punekar.

Bhavageet

Light, expressive, and poetic, bhavageets cover a wide range of themes—romantic, philosophical, devotional—and the songs are typically set to the dadra, kerwa, and roopak talas. Some well-known bhavageet performers are Manik Verma, Suman Kalyanpurkar, Malti Pande, Kunda Bokil, Sudhir Phadke, R. N. Paradkar, Arun Date, and Gajanan Watve.

Pandavani

Pandavani songs (the name refers to the Pandavas, the heroes of the Mahabharata) narrate incidents from the Mahabharata in a vigorous, rousing style, performed with dances and theatrical enactments. The principle singer plays the ektara, using it as an acting prop when needed—as Bhima’s gada (mace) or Arjun’s dhanush (bow), for example—and the backing singers help move the story along. The kartal, manjira, harmonium, tabla, and dholak provide additional music. There is a lot of improvisation, with the singers sometimes weaving current events into the narrative. Though traditionally a male preserve, there are female Pandavani performers like Teejan Bai and Ritu Verma.

Rabindra Sangeet

Rabindranath Tagore’s musical compositions—over 2,000, on varied themes—form the basis of Rabindra Sangeet. Collected in the four-volume Gitabitan (Garden of Songs), the works owe their inspiration to Hindustani classical, folk songs, and Baul music. Mita Kunda, Suchitra Mitra, Kamalini Mukherji, and Saunak Chattopadhyay are some prominent Rabindra Sangeet performers.

Temple and Festival Music

Social and religious festivals happen year round in India, celebrating the changing seasons, the harvest, religious days, mythological incidents, and the lives of saints and gurus. The Pooram temple festivals of Kerala—two of the famous ones being Thrissur Pooram at the Vadakkumnathan Temple in Thrissur and Arattupuzha Pooram at the Sree Sastha Temple (also in Thrissur)—feature performances of melam ensembles (which include chendu, madhalam, idakka, and timila drums, long curved kombu horns, and kuzhal double-reed pipes). These include Pandi Melam, in the temple courtyard, and Panchari Melam inside the temple, with vocal performances, dances, and processions of elaborately decorated elephants among the attractions.

Other festivals in Kerala include the Chembai Music Festival at the Guruvayoor Temple, and Onam. Other important musical events include the Konark Festival at the Konark Sun Temple; the Rajarani Festival at the Rajarani Temple in Orissa; the Khajuraho Festival at the Khajuraho Temples in Madhya Pradesh; the Jaisalmer Desert Festival and the Gangaur Festival in Rajasthan; and the Sawai Gandharva Festival in Maharashtra.

Wedding (Brass) Bands

The military bands of British India inspired the formation of wedding brass bands. The uniformed band musicians play a repertoire of popular film, pop, and folk songs on clarinets, horns, trumpets, trombones, tubas, saxophones, and snare drums.

Regional and Ethnic Forms

Adivasi

The Adivasis (original inhabitants) of India include over 200 tribes, such as the Santhals, Gonds, Bhils, Chakmas, and others. The Adivasi culture predates the Hindu and Muslim cultures, and has continued to exist parallel to them, interacting often but not integrating. Adivasi music is, for the most part, lively and vigorous, accompanied by dhol, tumdak, and tamak drums and bansuri and tiriao flutes, and based on Adivasi folktales, religious beliefs, and customs. Traditionally, the music is performed with communal dances at religious and seasonal festivals, and during courtship and marriage rituals.

Rajasthan

The vibrant, full-throated songs of Rajasthan, which evoke its vast desert landscapes and colorful history, have a classical base, often beginning with an alap, and making use of Bilawal, Desh, Kafi, Khamaj, Peelu, Maaru, and Gond Malhar ragas. Prominent among the different traditional musical castes are the Sunni-Muslim Manganiars, who, historically, played in the Rajput courts in Jaisalmer, Ajmer, and Udaipur, and during social events and festivals like Holi and Diwali for the Bhati and Rathore communities, Sindhi Muslim merchants, and other jajmans (patrons). The songs are rousing affairs about battles, chivalry, Rajput heroes, folklore, and folktales. They also sing of the seasons, sowing and harvesting, Krishna and Gorakhnath bhajans, and everyday events.

The Langas from the Barmer District sing on Sufi themes for mainly Muslim patrons, and are renowned for their haunting tunes on the Sindhi sarangi (4 stringed, with 20 sympathetic strings, and played with a ghungroo-embellished bow) and the algoza flute. Rajasthani songs use nagara, daf, dhol, tabla, mridang, and pakhwaj for keeping thetala. Panihari, Indoni, Gorbuns, and Kurjanv are famous Rajasthani folk songs; some well-known singers are Siddique Manganiar, Samandar Manganiar, and Rukhmaanbai Manganiar.

Baul

Hindu Vaishnavites, Buddhist Tantrikas, and Persian Sufis contributed to the development of the spiritual, devotional Baul music in pre-Partition Bengal. Traditionally, the wandering Baul minstrels accompanied themselves on the ektara, dutar, duggi drum, manjira, and bansuri, and received alms for their performances. The annual Joydeb and Poush fairs in West Bengal feature Baul singers from around the world. Parvathy Baul, Anando Gopal Das, and Manju Das Baul are some of the leading Baul performers.

Kerala

Kerala is renowned for its sopana sangeetam, a music form influenced by Carnatic, Bhakti, folk, and tribal traditions; sopanam means "steps," and the devotional songs (usually dedicated to Baghavathi Devi, Krishna, Shiva, and Vishnu) are traditionally sung from the temple steps and also inside the temple sanctum by hereditary male singers of the Marar and Pothuval castes. Desakshi, Puraneera, Indalam, Ghantaram, and other Carnatic ragas are employed—the performance samay (time of day or season) is specified in sopanam ragas—and chendu, madhalam, and idakka drums provide accompaniment. Kathakali, kalam pattu, Krishnanattam, and mudiyettu are some music forms that developed from the sopanam style. Ottamthullal and the poetic Mappila are other popular Kerala styles.

Assam

Assam has a rich folk culture with a variety of ethnic music forms like Jhumur and Bharigaan; regional geet like Baramahi, Tokari, Kamrupiya, and Malita, Bihugeet and Husori; Bhakti geet like Borgeet and Hiranaani; and the classical Ojapali. Instruments commonly used are dhol, dotar, mridanga, nagera, and baanhi flute, and well-known singers include Mahapurush Srimanta Shankardev, Madhabdev, and Dr. Bhupen Hazarika.

Uttarakhand

Uttarakhand folk music forms include khuded, thadya, jhoda, panwaras, and mandals. Popular themes cover legends and folktales, Himalayan scenery, religion, and social life. The dhol, turri, ransingha, dholki, thali, masakbhaja, tabla, and harmonium provide musical accompaniment. Narendra Singh Negi, Girish Chandra Tewari, and Heera Singh Rana are famous singers from Uttarakhand.

Article written for World Trade Press by Sonal Panse.

Copyright © 1993—2025 World Trade Press. All rights reserved.

India

India